This report was written by Julia Rock and Andrew Perez.

Republicans have said Americans shouldn’t worry if the Supreme Court strikes down the Affordable Care Act next year, because they’ve offered their own legislation to protect people with pre-existing medical conditions.

However, the bill being touted by the GOP’s most politically endangered senate incumbents would significantly weaken those protections. Among other things, the legislation authored by Sen. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., permits insurers to avoid existing caps on out-of-pocket costs for patients, institute annual or lifetime caps on spending, circumvent coverage requirements for essential benefits and charge women higher premiums than men.

That could be a lucrative windfall for the insurance industry that has already been recording outsized profits during the COVID-19 pandemic. That same industry has been funneling big money to the ten Republican senators who are in competitive reelection battles and who are among the co-sponsors of the legislation. Those incumbents have vacuumed in almost $2.6 million from insurance industry donors, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics.

In all, the ten largest health insurers and their top lobbying group in Washington have pumped nearly $10 million to Republican candidates and political groups in the 2020 election cycle.

“The Tillis Bill Likely Would Mean A Return To Pre-ACA Insurer Practices”

The ACA has done little to drive down health care costs, and tens of millions of Americans remain uninsured or underinsured. The law also preserved a health insurance system based largely on employment, which has led to significant coverage losses during the coronavirus pandemic.

However, the ACA did make 12 million more low-income Americans eligible for Medicaid — and its most popular provision prohibits insurance companies from denying coverage to patients with pre-existing conditions or charging them higher premiums because of those conditions.

As Democrats have slammed the GOP for trying to repeal those particular protections — and raised the very possibility that Judge Amy Coney Barrett will help the Supreme Court repeal the law — Republicans have been on the defensive.

During Barrett’s confirmation hearings last week, Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, insisted that Tillis’s bill — called the Protect Act — “will put into law, once again, protection for pre-existing conditions in our health care coverage.”

He added: “This notion that pre-existing conditions (are) somehow at jeopardy is simply rolling out yet again in this campaign cycle another one of the arguments that does not hold water.”

While the Protect Act would not allow health insurers to offer plans that impose “pre-existing condition exclusions,” the legislation does not include a number of key protections for patients with health problems that are currently law under the ACA.

“What it does, is it picks up one of the provisions that has gotten the most attention from the media and voters, and symbolically puts that back in place without giving it any real meat,” Allison Hoffman, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania, told The Daily Poster.

A report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that the bill would allow insurance companies to: “Impose annual and lifetime limits on how much they will pay out... sell plans with no limit on how much enrollees could owe in out-of-pocket costs if they get sick... charge higher premiums based on non-health factors that can strongly correlate to health risk, including gender (and) charge older people (most of whom have pre-existing conditions) far more, compared to younger people, than the ACA allows.”

Summarizing the situation, CBPP’s Sarah Lueck wrote: “In most states, the Tillis bill likely would mean a return to pre-ACA insurer practices. Under the bill, a person who has cancer technically could buy a plan and not be charged a higher premium due to the illness. However, his or her benefits could run out because the insurer imposes an annual or lifetime limit, or the plan might not cover the prescription medicines that treat the cancer.”

“Something Of A Mirage”

Tillis’s new bill is part of a Republican pattern of introducing legislation that sounds like one thing, but does another. There was the GOP’s “healthy forests” initiative that weakened environmental protections. There was the “clear skies” initiative that critics said would increase air pollution. And then there was Tillis’s original 2018 legislation called the “Ensuring Coverage for Patients with Pre-Existing Conditions Act,” which served as the foundation for his current proposal.

That 2018 legislation would have allowed insurers to reinstate “pre-existing conditions exclusions,” according to Larry Levitt, an executive vice president for health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“In other words, insurers would have to cover people with pre-existing conditions, they just wouldn’t have to cover the conditions themselves,” Levitt wrote. “That would make coverage of pre-existing conditions something of a mirage.”

He added that the bill would have allowed insurers to set premiums “based on age, sex, occupation, and lifestyle.”

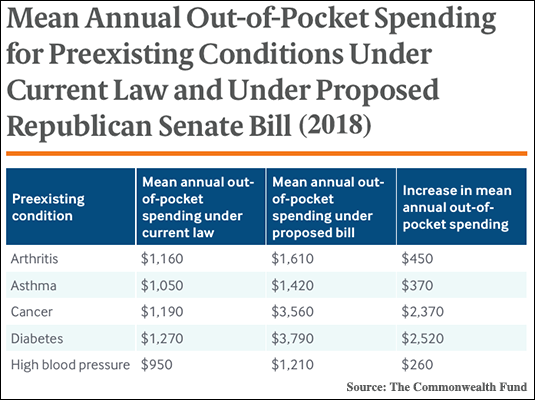

Allowing insurers to exclude coverage of certain benefits from plans would drive up out-of-pocket costs for people with pre-existing conditions. A Commonwealth Fund study estimated that under Tillis’s 2018 bill people with arthritis would see an average $450 annual increase in out-of-pocket spending while people with more serious conditions like diabetes could see a $2,500 annual increase.

Last year, Tillis introduced the newer bill, the Protect Act, to tackle some of the issues raised by critics. His newer bill would prevent insurance companies from denying coverage to people with pre-existing conditions, but it still wouldn’t substantially protect people.

“Unlike the ACA, the new Republican pre-existing condition bill would not disallow lifetime or annual limits, cap patient out-of-pocket costs, require coverage of essential benefits, prohibit gender rating, or provide subsidies to make premiums more affordable,” Levitt wrote last year.

Hoffman said the Protect Act only replicates “a little sliver” of the ACA’s protections.

“It says, you can't impose pre-existing coverage exclusions related to conditions that were present beforehand,” she said. “But it doesn't say to insurance, you have to cover A to Z, and you have to cover it without certain annual caps on spending and without lifetime or annual limits on spending.”

“A Symbolic Effort”

“I’ve always supported protecting anyone with a pre-existing condition.” Sen. Martha McSally, R-Ariz., says in a recent advertisement, adding that her Democratic opponent Mark Kelly “knows I opposed Obamacare because it raised taxes and took coverage away from Arizonans, but he’s using that Obamacare vote to scare you about pre-existing conditions.”

Montana Sen. Steve Daines releasedan ad similarly accusing his Democratic opponent, Gov. Steve Bullock, of lying: “He's using my vote to fix the Obamacare mess to lie to you about pre-existing conditions. Here's the truth. I've always fought to protect Montana's with pre-existing conditions, and I always will.”

Daines and McSally have both voted several times to repeal the ACA. So has Tillis.

Polls show that a large majority of voters from both parties, as well as independents, oppose a repeal of the ACA’s protections for pre-existing conditions.

Daines and McSally have co-sponsored the Protect Act, alongside other Republican senators in competitive reelection races, including Joni Ernst of Iowa, Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, and David Perdue of Georgia. The bill’s lead author, Tillis, is locked in a tight reelection battle with Democrat Cal Cunningham.

“When I look at this bill, I see a symbolic effort by Senator Tillis to say, here we have something, because of all the claims that the Republicans have come up with nothing to respond to potential replacement of the Affordable Care Act, but this is close to nothing, what he proposes,” Hoffman said. “It’s not nothing, but it’s close to nothing.”

Photo credit: Wikipedia/Jackson A. Lanier

This newsletter relies on readers pitching in to support it. If you like what you just read and want to help expand this kind of journalism, consider becoming a paid subscriber by clicking this link.